Mel Gibson has never been a filmmaker who treats faith as something fragile or ornamental, and his latest revelation about the Shroud of Turin and the Resurrection proves that he remains unwilling to soften the edges of belief. In his telling, the Shroud is not the product of medieval artistry or centuries of decay, but the residue of a moment so violent and overwhelming that it defies modern language. He describes the Resurrection not as a gentle awakening but as a rupture in the laws of physics, a detonation of energy that imprinted itself onto linen in a way no brush or pigment ever could. “This was not serenity,” Gibson insists. “It was power unleashed, a force that left its scar on history.

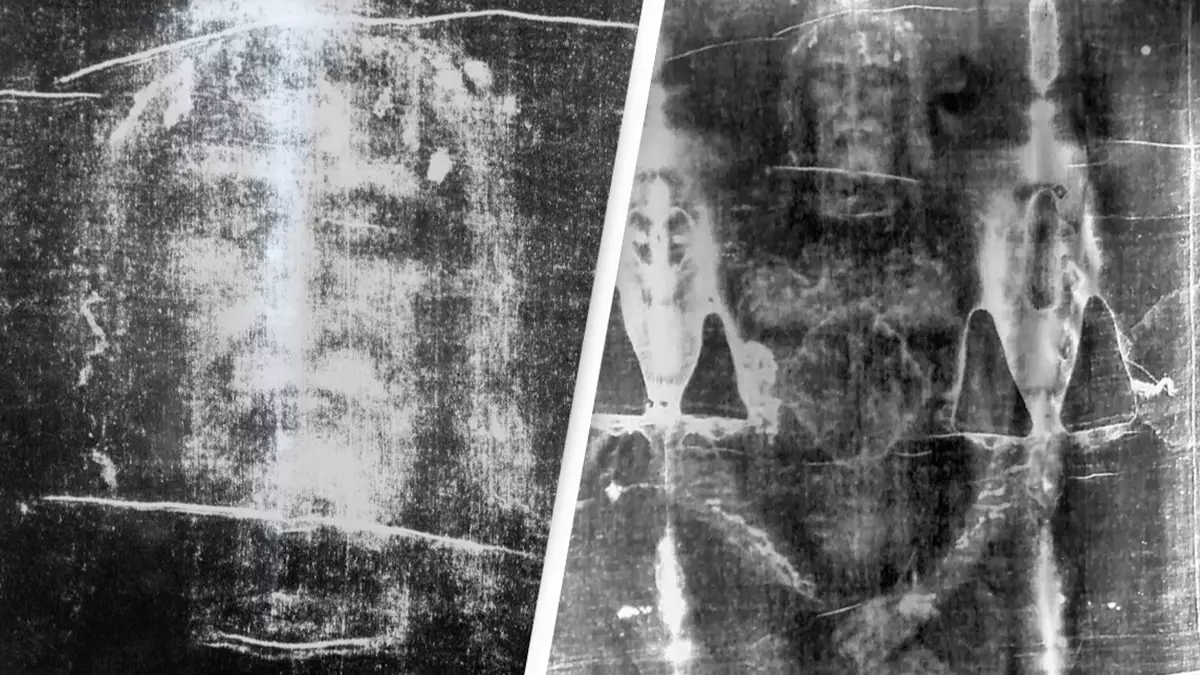

What unsettles many listeners is not only the claim itself but the way Gibson speaks about it. There is no triumph in his voice, no attempt to reassure or comfort. Instead, he paints a picture of something frightening in its magnitude, a reminder that if the Resurrection was real, it was not gentle. The Shroud, in his view, is the silent witness to that threshold between death and something beyond comprehension. He suggests that the image was formed by a vertical emission of light or energy radiating outward from within the body, marking the cloth without scorching it. Scientists have long struggled with the fact that the image contains three-dimensional information and no directionality, characteristics consistent with a burst rather than a brushstroke.

Gibson’s fascination with this idea deepened during the development of The Resurrection, the long-anticipated continuation of The Passion of the Christ. He immersed himself in scientific papers, fringe theories, and theological texts, searching for a way to visualize the impossible without reducing it to spectacle. What he claims to have discovered disturbed him. The Resurrection, he says, would have been an event of unimaginable force, closer to a cosmic detonation than a quiet miracle. In that context, the Shroud becomes less mysterious and more inevitable, a scar left behind because something that powerful cannot pass through the physical world without leaving a trace. “The cloth is not art,” he explains. “It is evidence of impact.”

This theory unsettles even believers. Many prefer to imagine the Resurrection as serene, symbolic, a moment of relief rather than rupture. Gibson rejects that instinct entirely. He argues that if death itself were defeated, the process would not be subtle. The Shroud, in this framework, is not meant to comfort but to confront. It is the residue of an encounter between the divine and the material, frozen in linen. The fact that it resists full scientific explanation is, to Gibson, precisely the point. “If it could be explained away, it would not be the Resurrection,” he says.

What makes his revelation more controversial is the implication that modern audiences are not prepared for what the Resurrection truly represents. He believes that previous depictions have softened it, turning it into a moment of beauty rather than terror. In The Resurrection, he intends to show it as something terrifyingly real, an event that would have left witnesses shaken, not soothed. He has hinted that the moment will be portrayed with overwhelming intensity, emphasizing awe and fear rather than comfort. The Shroud, then, becomes the visual echo of that moment, a forensic trace left behind by transcendence.

Critics accuse Gibson of blurring the line between speculation and fact, but he seems unbothered. He insists he is not offering proof, only coherence. To him, the Shroud makes sense only if something extraordinary and violent occurred at the moment of Resurrection. He points to the absence of decomposition, the superficiality of the image, and the strange way it encodes depth as clues that the event defies conventional categories. “This is not science fiction,” he argues. “It is an honest confrontation with data that refuses to behave normally.”

There is also a deeply personal undertone to Gibson’s explanation. He speaks about the Shroud as if it mirrors his own experience with faith and exile—marked, controversial, impossible to ignore, and never fully accepted. Just as the Shroud sits uncomfortably between belief and skepticism, Gibson sees himself suspended between reverence and rejection. This parallel is not lost on him. Revealing his theory now feels intentional, almost defiant, as if he is daring audiences to look directly at something they have trained themselves to soften or dismiss.

The most chilling aspect of Gibson’s revelation is the implication that the Shroud was never meant to be understood easily. If it truly is the result of a Resurrection-level event, then confusion, debate, and discomfort are not failures but features. The image is faint, distorted, and incomplete because what created it was beyond human scale. Gibson suggests that trying to reduce it to a tidy explanation misses the larger truth: that some moments are meant to unsettle history, not resolve it. “The Shroud is not there to answer questions,” he says. “It is there to remind us that some questions cannot be answered.”

As The Resurrection inches closer to reality, Gibson’s words hang heavily in the air. If his depiction aligns with his explanation of the Shroud, audiences may find themselves confronting a version of faith that is raw, destabilizing, and deeply physical. The Shroud of Turin, long treated as a quiet relic behind glass, suddenly feels louder, more urgent, and more disturbing. And if Gibson is right, it is not asking to be believed or dismissed—it is asking one terrifying question in silence: what really happened in that tomb, and are we ready to see it the way it truly was?